- Home

- Annaleese Jochems

Baby Page 9

Baby Read online

Page 9

‘It’s hot,’ Cynthia says. ‘It’s so hot.’

Toby nods, relieved, and Cynthia sees Anahera watching her. She smiles back, and climbs up onto the edge of the boat, then jumps into the water. It’s cool and fresh, and Cynthia doesn’t generally jump off things. Toby jumps in after her. Then, after thinking about it, Anahera does too.

23.

Even though he’s in a man’s body, Toby stands and watches Cynthia and Anahera drag the dinghy up the beach, twitching his foot, with the dark mass of trees waiting behind him. They put it down, and while Cynthia’s puffing, he shoots Anahera a thumbs up and runs at a jog-trot into the trees. ‘Go that way,’ she yells at him, and he swerves to enter the bush where she’s indicated.

Cynthia lets them go ahead together. Her feet are bare in the warming sand, and she hasn’t been alone for so long. The water flickers. She’ll have a new, fresh opportunity to understand Anahera soon, and she knows she can do better. Waves touch the beach and leave it wet, like licks over skin. She and Anahera will come back later, just the two of them, and the ocean won’t have paused. She lies back to watch the clouds, just for a while.

Rested and warm, she follows their footprints along the beach, into the trees. In the clinging, striving mess of bush there’s Anahera’s bright orange workout singlet to follow, and then it disappears. When Cynthia sees it again it’s stopped still. She can’t see Toby. She concentrates on moving carefully, watching her toes and where she puts her feet, and holding the thicker trunks for support at the rocky parts. When she’s closer she sees Anahera looking up, and she looks up too.

First she sees nothing but green, then—Toby’s high in a tree. Anahera looks at her briefly when their shoulders touch, but turns quickly back to see him. This is the only way to admire people in his age group, Cynthia thinks: from a distance. He moves quickly and doesn’t pause. He’s done this before.

‘Adults have forgotten the purpose of sports,’ Anahera says. Cynthia looks at the side of her face and wishes she could be up there too; that she were a sportsperson. She can feel Anahera’s arm against hers and, she thinks, a heightened pulse in it. The tree’s high and tilting leftwards. He’s near the top, at the surface of the canopy.

Down low, where Anahera and Cynthia are, there’s no space for the air to move and they don’t either. Anahera’s breathing is steady. Cynthia knows what she wants, and she shouts up at him, ‘Higher!’ Her voice is a sudden break in the quiet, and she wishes she could suck it back in. It doesn’t matter, he’s too far to hear her, anyway.

He stops and waves, then looks down. He’s ready to turn back, Cynthia can see it in his smallness, in how vague and unreal he looks. He lowers his left leg, and feels with that foot for a branch to stand on. ‘To the right!’ Anahera shouts, but Cynthia doesn’t feel so patient. He’s done now, he should just come down. He puts that foot back where he had it, and pauses, then lowers the other foot, and feels right. Anahera blows out air, and runs a hand through her hair. His hand slips as his weight shifts to the right, and she inhales again. He grasps again for the branch, but his left leg’s shaking at the knee. He moves to pull his right foot back up, and the left slips. He’s hanging from two branches, and one of them snaps. He falls, plonks.

The thud echoes, and the ground feels too solid under Cynthia’s feet. Where is he? His tree, despite its height, has disappeared into all the others. There’s no wind, and she forgets Anahera. For a moment nothing’s alive, and all the trees might be made of plastic. They’re so still, and such pure green. Cynthia touches her eyes and they’re dry. They blink. Her hands hang slack at her sides, like two wet towels. She sees his body then, a lump in the distance.

One of his elbows points skywards, she sees now, and his legs are tensed. A leaf shifts—and like that, there’s wind again. The forest is alive once more with bugs, but when Cynthia touches her eyes a second time, they’re still dry. Anahera’s walking towards him. Cynthia follows, and when they arrive they see his eyelids. The right’s shut, and the left’s mostly open. Behind them, both his eyeballs stare up, and Cynthia and Anahera stand looking back down at him for a long time. His mouth is wide open and empty. Anahera squats for a moment, obscuring him with her back, then stands again.

Cynthia would like to know what to do. She moves away, and sits on a log to wait. She’d like to have a good thought, but she thinks only of how it wasn’t her fault, or Anahera’s. The sandwiches were squashed to mush in her fist while she stood looking at him, and she takes a bite of one now, chews, and spits it out. It sits in the dirt, as pink as guts. She pushes it aside with her shoe, and some gets caught on the toe. She won’t feel guilty, she decides, and when Anahera sits down beside her, she pulls her sandwich apart and peers into it, to see the fleshiness, then takes a bite and swallows.

She can feel without looking how Anahera’s lips are pulled in, and trembling like they’ll be sucked down her throat. She tries to speak three times before she says, ‘What can we do?’ The edges of her eyes look sore, and her nose has swelled up red.

Only what they’re doing, but Cynthia doesn’t say it. She stands up and takes off her sweater, then walks to him. His mouth is slack at the corners, like it’ll fall off his face. In his eyes, behind the wonky lids, there’s a look she recognises from when he first arrived on their boat and looked about him. A slumped look, disappointed and aggrieved. She lowers herself to her knees on the rough, rock-studded earth. Her sweater is pink merino, thin and soft, and she puts it over his face. But his neck looks too exposed, pale, and his Adam’s apple seems painfully sharp, like a stone pressed up through his body from the rough ground below. She piles leaves over him, so his thick limbs and neck are buried like roots. One of his hands sticks out, uncovered and limp, turned palm up, and she can see the veins running to it through his wrist. She’s covering the hand when wind blows in a gust and exposes his knees and chest in patches. She piles the leaves back on, grazing his chest with her wrist. It’s still warm.

She’s finished, he’s completely covered, and she sees the pink of her sweater and how wrong it is. It looks like the jam from her sandwich; it looks spat out. She can feel his face under it, can see the outline of his nose pushed through. There’s still heat in him. In the dark under her sweater, behind his half-shut lids, he’ll still have heat in his head. His brain, as pink as her sweater, is probably still twitching in the dark.

She takes it back. She doesn’t want to look down but she does, and his face is exactly the same as before, except his mouth might have gone a little slacker. She goes back to sit with Anahera, and Anahera says, ‘He’s just lying there.’

Cynthia squeezes her sweater in her fists, it’s still soft, and puts it back on. They sit for hours. She eats the rest of the sandwich she bit twice earlier, and it’s too sweet. She used too much jam. She holds it between her teeth like a kitten in a cat’s mouth, and leans backwards. She lands heavily with her head on the ground, and grabs Anahera’s still, steady arm to pull herself back up. It doesn’t work, she needs to be helped. Anahera doesn’t move.

‘Okay,’ Cynthia says. The blood’s all run to her head, and the jam’s sickening in her stomach. She flops right down, and gets back up. Standing, she shakes her legs and stomps them into the ground to get the leaves off. She plucks every leaf from her sweater, and when she’s done she drops it back onto the ground, back into the leaves. Anahera’s sitting with her eyes closed, and her head lifted. Her mouth moves in little tremors. She’s praying.

24.

Cynthia pretends not to have noticed, and waits while Anahera mouths thousands of little words that can’t mean anything. After hours, Anahera’s eyes open slowly, but she looks down at her own hands, not at Cynthia.

Cynthia’s lonely, so she gets up and walks. It’s not a big island. She’ll come back soon and they’ll paddle home. She walks over lumps of roots and rocks, and through twiggy, sticky branches, falling and picking herself up twice without understanding that she’s tripped.

He fe

ll, and Cynthia thinks about the silent stillness of his body caught in the leaves. Now everything is moving again, there are sounds again, but that only means his quiet has turned into something else. She can’t remember where he was. She looks up and feels she’s being watched. She’d like to go back to Anahera now, but she turns and turns and every direction she picks feels the same as the one she came in. Then she sees something in the distance, blue, behind the vine-tangled trunks.

She walks closer. It’s a tent. Beside it there’s a dead campfire, dug into the ground, and a pile of wood. She approaches with her hands behind her back, and keeps them there, but bends to look closely. There’s a pot, dirty with tomato sauce and dropped on its side. A stack of canned spaghetti and beans. Sloppy food, she thinks, and remembers Toby’s fake gagging. The trees are loud around her.

She walks around the tent twice, then stops to touch its door flap with her fingers. It’s unzipped and hanging open. She wants to hide, wrap up, and suck both her thumbs. Inside it’s empty except for some blankets, a pillow and an exposed mattress. It would relieve her to crawl in, she thinks—maybe in there she’d cry.

But, Anahera. Cynthia didn’t see her face when he fell, and not even for a time afterwards, but she saw the way it had swelled from crying when she left her alone on the stump.

Anahera doesn’t look up, she hasn’t moved.

‘I found a tent, with a fire and a bed,’ Cynthia says.

Anahera’s twirling a leaf on a stalk, between her fingers. ‘Did you.’ She lets it go, and they sit longer.

Cynthia says, ‘Do you think we should go back to the boat?’

She waits, but Anahera doesn’t answer. It’s getting dark, and quickly. Each tree has a shadow, long and distorted, mingling with the others, growing. She lifts Anahera by the arm, and leads her back through the dark mess of bush to the tent. They don’t trip, fall or get lost, they simply trudge and arrive there, like they’ve been led. There’s a can opener she didn’t notice before, balanced perfectly on top of the spaghetti and beans stack. She opens some beans and they share them. Anahera weeps, and some fall from her mouth into the dirt. Cynthia wipes the sauce from her chin and asks, ‘Do you want to sleep?’

The trees have disappeared into their own shadows. It’s night. Cynthia leans closer, and asks again, quieter, ‘Do you want to sleep?’ but Anahera doesn’t look at her, and shakes her head.

Cynthia crawls into the tent alone, and tidies the blankets as best she can in the dark. She’ll give the pillow to Anahera. ‘Anahera,’ she says, and she says it again and again till she’s not sure Anahera’s still there anymore. She can’t settle, and the blankets get messed up. She tidies them a second time, and leans out under the sag of the door flap. There’s Anahera’s hair, a dark mass looking so soft Cynthia thinks everything would feel okay if she could just touch it. She pulls at Anahera’s shoulders, but they don’t move.

When Anahera comes to bed she faces away from Cynthia, and Cynthia gives her as much privacy as possible, pushing herself against the side of the tent, so tight it makes a damp mask over her face.

Later she wakes and Anahera’s holding her so close it hurts.

25.

The next day Cynthia stirs slowly, and late, into the musk of the tent and her own sweaty heat. Anahera’s gone. The nylon above her is illuminated in sections where light’s struck through the trees. It’s blue, and very bright in places. Lower down, it’s mildewed, in some parts pure green. Her legs and arms are moist in the blankets, and she sniffs. The air’s potent with the smell of mould, beans and something else. Anahera’s left the door flap open, and through it Cynthia can see the pile of used cans. They’re stacked, but most have fallen and rolled. A bird lands on top of them, and shoves its head inside so deep and quickly Cynthia worries it won’t be able to retrieve it. A can shifts. The bird yanks its head out fast, and flies off. Everything is still again, but Cynthia thinks she can feel bugs on her. So many of them that they’re like a new, thin layer of her skin. She looks at a plant so spindly it shouldn’t be able to stand and remembers the boy, that he’s dead. There are no insects to brush away, there’s only Cynthia alone in the forest, and the time to wait before Anahera comes back, if she does.

The cans are still, and the trees shift only slightly behind them. Cynthia looks at the tent roof, then back at the thin tree. Anahera walks briskly into view then, and says, ‘We’re going. Get up.’

Cynthia does. There’s nothing to bring with them. She follows as quickly as she can, not saying anything, but trying after each big tree they weave around to clutch Anahera’s hand. Anahera’s legs are her usual legs again, solid and abrupt, and when her hands swing back behind her they’re fists. She doesn’t look around, only straight ahead. They walk and walk, and the green brightens as they approach the edge of the bush, the beginning of the beach, and the sun. Cynthia thinks of asking about Anahera’s feelings, but it doesn’t seem appropriate. Anahera looks about suddenly, twice and twice again as if she’s seen something. A pest, or a predatory animal. Cynthia looks too, at least three times in every direction, but only sees birds. The previous day she didn’t notice them, but they’re everywhere now. Some stop and peer at her, tilting their heads one way and the other. There are so many of them waiting along the path, and each flies off in its own direction. Then they all pause, even their necks with their shifting heads don’t move, not at all. The leaves are bright, they’re near the beach and it must be around midday. Cynthia’s back is hot, and there’s sweat on her top lip. She stops to suck it, and Anahera takes another step forward, and screams. There’s a moment of her standing still, then she contorts and crumples.

The trees are huge above them. All of them loom. There’s a steel trap clamped at Anahera’s ankle. It’s not bleeding, but the trap’s made a horrifying dent in the muscle, and Cynthia’s worried about the bone. Anahera moans, crying, and Cynthia squats down. She touches the metal and the skin, then sits back to look. Finally, with all her courage, she leans forward and pulls hard on the bars connected to the clamps. The trap comes out of her left hand, and her effort to open it slams it into the ground. Anahera screams again, for seconds and seconds, but there’s nothing to help them. The trees grow more alive, closer. ‘Shh,’ Cynthia says. ‘Hush, I’ll take care of you.’ Anahera looks at her, wild. The birds are moving again now, they’re everywhere with their dark, darting eyes, watching. Anahera stares hard at Cynthia, and shakes her leg and the trap till she cries out again, and her elbows slip, so her head hits the ground with a thump.

Cynthia touches Anahera’s hair, it’s still soft, and she can still at least touch it softly, and says, ‘I want to be good, I want to help.’ But Anahera’s moaning sharpens. Her whole body shakes, the foot most of all. The trap drags along the ground, lifting and thumping back down, and each time the sound Anahera makes is louder, and hurts worse.

‘Please let me help you,’ Cynthia says. Anahera’s foot stops moving at a last thump after hearing this, but her screaming continues at the same aching volume. Her eyes dart everywhere around them. The birds are at a distance now, still looking and tilting their heads, but from behind leaves and branches. The noise is so much inside Cynthia’s head. It goes on despite her.

Anahera stops suddenly and asks, ‘How? How can you help me?’

Cynthia can’t think. A hard, big reality has fallen on her. Might they die there? If they do they’ll be alone, separated eternally by Anahera’s noise. She moves forward gently, towards Anahera. It has to come off, so there must be a way to get it off.

‘Don’t,’ Anahera says quietly.

Cynthia begins saying something about love, her love, and the anything and everything she’s willing to do, but Anahera screams again, and her eyes bulge. She’s looking behind Cynthia.

A person steps out of the trees. ‘I am a German man,’ he says, and comes forward. His moving is confident, his feet are big and in big floppy sandals but they fit perfectly between the rocks each time he puts them down. He t

ouches the trees, but not for support; he touches them like loved and known furniture, like all of this place is his own bedroom. He’s carrying a huge backpack with two pairs of shoes tied to it and holding a fishing line. He nods. ‘A big one!’ he says, gesturing to the trap. ‘There.’

He’s arrived and he’s an answer, Cynthia understands. Anahera looks like she’s about to pass out.

‘Not legal,’ he tells her sternly.

Anahera groans, glaring hard, but Cynthia sees she’s looking at the man now. He’s moving slowly. He gets on his knees beside Anahera’s foot, without looking at her face. ‘It’s not serrated, you are alright,’ he says. She yells and spits up at him, but it lands on her chest. He shifts back and waits for her to finish. ‘Don’t fight me.’ He moves over her again, and Cynthia can’t see the trap anymore. Anahera doesn’t move, but she’s breathing deeply, like something about to attack. His biceps flex, and Cynthia hears the metal pop open. ‘This bad boy is not from this century,’ he tells them, and he opens his pack and puts the trap inside.

‘Have you already eaten?’ he asks.

They don’t answer.

‘I have not,’ he says, and takes a Tupperware container from his bag. It’s white rice, drizzled with soy sauce. He brandishes a spoon from his pocket. ‘I am a German man. Hello, I am Gordon. I’m only friendly. Don’t fight me,’ he says, then starts eating, ignoring Anahera as if she were an unnecessary table between himself and Cynthia.

Cynthia flicks her gaze from his spoon to Anahera’s bulged eyes.

‘Just sit quietly, you will be fine.’ He nudges Anahera, and she moans again. Cynthia’s very thankful he’s arrived. He can carry Anahera back to the dinghy and paddle them home to their boat. She’ll take it from there.

He talks through his food. ‘I am on a nice-nice holiday with my girlfriend. But she left me on this island! For another girl! But I have all the money! You see, it is a twist. I am on a nice-nice holiday with myself!’ He swallows and laughs, ‘Ha ha ha. Ha. What am I to do with all this money which I have?’

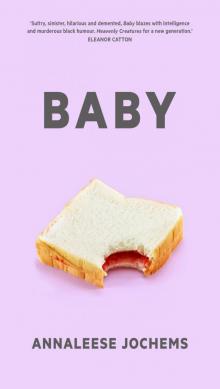

Baby

Baby