- Home

- Annaleese Jochems

Baby Page 3

Baby Read online

Page 3

‘Let me know when you want to drive,’ Anahera says.

‘Oh, I don’t—drive,’ Cynthia replies.

‘That’s fine,’ Anahera says.

There’s a word in Cynthia’s mind, an enormous one: divorce. They stop at a bathroom, and while she pees she says it to herself. She says it quietly, but it’s loud. The walls are unpainted wood, and she rubs them with her hands till the fat of her fingers catches a splinter, then she bites it out.

When she comes back out she’s still walking through the awe of it, and she’s awed even more to see Snot-head sitting cosy on Anahera’s knee. Perfectly, Anahera looks a bit embarrassed, coughs and shoves him off.

Three more hours of driving, and Cynthia says, ‘I think with the way my dad is—I think we’d better get cash.’ They’ll stop in Whangarei, Anahera says.

In Whangarei they wait in a queue at ASB. Cynthia keeps thinking Anahera’s leaning down to whisper something, or about to, but she never quite does. They shuffle forward, like everyone else.

The lady says hello.

‘Cynthia would like to withdraw everything from her account, in cash,’ Anahera says.

‘Would you?’ the lady asks. She’s got blond hair, but it’s cheap, supermarket.

‘I’ve decided to purchase a boat,’ Cynthia says, and hands over her card. She’s shorter than both the bank lady and Anahera.

‘She and her father have been discussing it for a while now,’ Anahera tells the woman, and pats Cynthia’s shoulder.

She nods. ‘Well, good on you!’ she says. She puts a phone to her ear and dials. ‘Pete, yes, Pete—I’ve got a youth here—’

Cynthia interrupts her: ‘I’m twenty-one.’

Anahera’s pat becomes a squeeze. A man walks through a door, past the tellers. He’s blond too, and very combed. The blond woman shifts off her seat so he can stand in front of her. ‘She’d like to empty it,’ she tells him from behind.

Pete looks at the screen and he laughs. ‘16,800, eh?’

‘For a boat,’ Cynthia says.

‘Hi, I’m Anahera.’ Anahera puts her hand through the gap in the glass. Cynthia introduces herself too, and when Pete’s laughed some more he says, ‘Look, ladies, it’s a bit humdrum, but I’m going to need you to sit down and sign some papers.’

They stand where they are and wait for him to walk along, back behind the tellers and through the door he came from. The blond woman smiles at them, then at the man behind them in the queue. Anahera pulls Cynthia aside to let him past, and Pete appears from a different door. ‘Follow me,’ he says, and gestures towards a third door. It’s windowed, and opens to a little room where they both sit in cushioned chairs and wait while he prints forms. The printer makes a rasping noise, but he speaks louder, saying, ‘Now, I’m going to need some proof of identification.’ He laughs. ‘If that’s not too rude a demand.’

Cynthia hasn’t got it on her. Anahera hands her the keys.

When she comes back Anahera’s touching her face, laughing, and he’s laughing too, with his crotch forward, his shoulders back, and his two hands gently caressing his belly.

‘She’s just finished uni,’ Anahera says, nodding at Cynthia.

‘Yeah,’ Cynthia says, handing over her 18+ card. ‘I have a degree.’

Pete nods, and Cynthia signs the papers he slides her. He checks them, turning each one over although some aren’t double-sided. ‘Righto,’ he says, ‘and next time—you can trust us—but next time, remember to read the small print on any documents you sign.’

Anahera nods and pats Cynthia’s hands, which are held together in her lap.

‘Righto,’ he says again, and goes off to put their forms somewhere, and presumably get their cash.

He comes back with a surprisingly large padded envelope. Cynthia squeezes it. There are five wads in there, rubber-banded. ‘Why not just a cheque?’ he says. ‘What sort of boat is this?’

The envelope’s clutched tight in her fist, and Cynthia wants it back in her account, or her father’s; intangible again, put back into nothing. She wants to eat it. There’s no wind on the street, and people are looking at her. Should she dig a hole and bury it, like a dog? Put it down on the street and piss on it? Anahera is waiting quietly. Should she run?

‘I’m sorry about in there,’ Anahera says.

‘What for?’

‘I don’t know.’

Cynthia sees her properly then, and understands her own terror as a ripping, a new place being made in herself for love. Anahera must be feeling the same way. A car goes past them quickly, loudly, but Anahera doesn’t seem to notice it, or the people all around them pausing to gawk. She’s not looking down at the envelope either, but at Cynthia’s face. Anahera’s eyes are brown in this light, on the street. She’s doing nothing but waiting, with the sun on her face, for Cynthia. Neither of them can run, or will.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ Cynthia says.

‘Do you still want KFC?’

‘Nah.’

They get back in the car. The passenger window is fogged with dog breath, and imprinted by his nose. Cynthia hands over the envelope, and Anahera puts it in the compartment between them.

‘What kind of boat do you want?’ Cynthia asks.

‘Probably the cheapest one.’

‘Yeah.’ Cynthia nods. ‘A little one then. Good.’

Anahera laughs. The dog’s quite heavy after all the sitting he’s already done on Cynthia, but he’s warm.

6.

Cynthia’s been trying to explain for a while precisely what it is that’s so tragic about Talhotblond, the documentary Randy so pathetically failed to understand. Snot-head’s wheezing gently, and Anahera’s been mostly listening for twenty minutes now. Cynthia jolts Snot-head awake, remembering something that could be crucial. ‘The spelling of tall in the title is actually incorrect, they miss one of the “l”s, because the lady herself misspelled it in her username! And then—in real life she was actually quite short, so.’

‘Okay,’ Anahera says.

Knowing Anahera gets it makes Cynthia get it even more. ‘But they’re in an impossible love!’ she says. ‘They can never actually meet each other, because she’s too old and he’s a loser! It had to end in death.’

‘Don’t you think people just need to make things work?’ Anahera asks.

‘What I know,’ Cynthia says, ‘is that there was no possible ending without Brian’s death, and everyone else’s heartbreak.’ She looks at Anahera and sees she disagrees. She disagrees, but she understands. She’s a force to be reckoned with.

‘You know,’ Cynthia says, ‘I think we three are going to save each other.’

‘From what?’

Cynthia doesn’t answer, they won’t know exactly till they’re saved.

Cynthia gets out first at the boatyard, then Snot-head, then Anahera, then Cynthia catches Snot-head and puts him back in the car. She’s got to hold his small body back after she’s put him down, inch her hands out the door and slam the last gap quickly. Anahera puts the envelope in her hands. They walk together up to a brown box-shaped office.

A guy sticks his head out the door. ‘Hi!’ he says.

‘Where’s your cheapest?’ Anahera asks him, coolly.

‘Oh yeah, I got a little pretty one for $18,000? Come in and I’ll show you a picture.’ He shifts aside and lets them in first.

It’s tight and tiny in his wooden office. He sits behind a desk and Anahera takes a plastic chair, gesturing for Cynthia to sit on a padded one. He pulls out a worn photo album with yellow and blue flowers on the cover, opens it and shows them a photo at the very back. ‘Comes with plates, anchors, some buckets, bedding, spoons,’ he says, and he keeps listing other things, but Cynthia is in love.

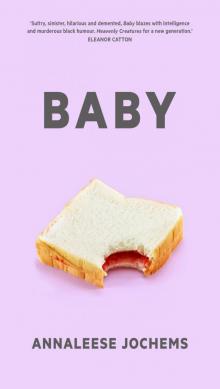

It’s got Baby written in wispy orange lettering on the side. It’s bluish-white, with dirty bits at the water line, and the sea clinging at its little hips like low-waisted pants. There are bigger boats around it, but Baby catches the sun better.

&nbs

p; ‘That looks alright,’ Anahera says.

‘Belonged to an old couple,’ he says.

‘You’ll have to reduce your price,’ Anahera tells him.

‘How much have you got?’ He nods at the envelope in Cynthia’s hands.

Cynthia’s about to answer, but Anahera says, ‘Doesn’t matter how much we’ve got.’

He pauses, thinking.

‘Cash,’ Anahera says, and Cynthia’s thrilled and proud to be with her, to be her girl. She shuffles in her seat and covers her mouth with a finger.

‘$18,000,’ he says.

Anahera shakes her head.

‘We could sell your car?’ Cynthia asks her, chuffed to have an idea and be involved.

The guy looks at Anahera.

‘Do you have a wife?’ Cynthia asks him, then. ‘Kids?’

He laughs. ‘My wife drives a better car than that.’

Anahera laughs too, but only for a moment.

‘We won’t do more than $15,500.’ Anahera straightens her face. ‘Looking at that picture.’

He stops laughing, and Cynthia can tell this is going to take a while. She goes out to find water for Snot-head. They sit and wait. ‘Bureaucracy,’ she tells him. ‘It does go on and on.’

Eventually, the door opens and the guy emerges with Anahera. ‘Ron!’ he yells. ‘Ron!’ Then he looks down at Cynthia and grins. ‘Not his real name, but you’ll see why I call him that.’

A red-haired boy arrives from a back corner of the yard, he’s excessively freckled, and eating Twisties.

‘See?’ the guy says, taking the packet.

‘Yeah,’ Anahera tells him. ‘That’s good, alright.’

‘Look, Ron, buddy, you take these ladies in that car’—he points at Anahera’s car—‘and show them where’—he’s leafing through his notebook—‘thirty-three is. You know the one? Baby.’

Ron’s watching his Twisties swing in the guy’s hand. He looks up, squinting—he doesn’t know Baby.

The guy says, ‘Anyway, thirty-three,’ and eats a Twistie.

‘Can I keep the picture?’ Cynthia asks the guy, nodding at the album hanging in a hand at his side.

‘Yeah, that’s ten extra. Nah, just kidding.’ He slips the photo out, clumsily, then nods at her envelope. ‘16,000,’ he says. ‘Plus the car.’

That sounds good, so Cynthia opens the envelope and lays the notes out on the step, counting them. There’s no wind, and Ron steps forward to shift Snot-head out of the way. Cynthia can feel Anahera standing above her, but she tries not to rush. It does take a while. She turns back, and hands the money to Anahera, who passes it on to the guy. ‘Good,’ he says, without seeming to look at the notes or the numbers on them. Then he yells, ‘Ron,’ again, jokingly, because Ron’s already there.

Just before they get in the car to go, he trots back up to them. ‘You people want a dinghy?’ he asks, blowing air out his nose.

Cynthia shrugs and Anahera says yes.

‘Yeah,’ he says. ‘You’ll need one. I forgot. Nothing extra. You want a motor in it?’

Cynthia’s about to say yes, but Anahera speaks first. ‘A paddle is good.’

Ron puts an old dinghy on the roof of the car, and Cynthia stands holding Anahera’s arm and looking down at Snot-head. When Anahera’s moved stuff around in the back seat to make room for him, Ron says, ‘Or should I drive?’

‘Nah,’ Anahera says, waves at the guy, and they go.

Snot-head snorts, snuffles, sniffles and finally settles on Ron’s knee. He’s quiet in the back. Cynthia turns and asks him, ‘How old are you?’

‘Sixteen and a half,’ he says.

‘You look nineteen,’ she tells him suggestively, and turns back around to flash a smile at Anahera. Anahera looks very ambiguous, and flicks the indicator.

Ron and Anahera carry the dinghy down a metal causeway, to the jetty. It’s narrow, so Cynthia walks behind them. They tie it up in the water, and when they turn around she’s embarrassed to be standing there with nothing, so she marches back to the car. She opens a door, and as soon as she does Snot-head runs out and begins pooping. Anahera and Ron both nod to show they understand, he’s got to do it. He starts and stops, first under the tree, then a rubbish bin, then back under the tree again. Anahera and Ron take a second load, then a third. Before he takes the rest of the stuff, Cynthia stops Ron. ‘Give me your number,’ she says. ‘We’re probably gonna throw some parties on there.’ He does. Anahera pauses and goes off again.

‘That’s the thirties,’ he says, gesturing off at some boats anchored a little way from the wharf.

‘Right.’ Cynthia points at exactly where she thinks he means.

Anahera comes back, and stands beside Cynthia. ‘Maybe you’ll show us how it works?’

‘Um,’ Ron says. ‘I’m not too good with those older ones.’

7.

Baby appears gradually from behind all the bigger, more robust boats, dancing like something imaginary. The water lifts her sometimes, then drops back under, exhibiting her dirty underneath.

Snot-head runs around fast, sniffing everything, and Cynthia watches on. Big houses with a lot of glass windows look down on them from the hills. That must be where the boat salesman lives, she decides.

Anahera goes back in the dinghy for the rest of their stuff. There are windows, curtains and lots of little cupboards for Cynthia to open. There’s a trap-door in the ceiling, so they can keep things up there. A little cabin, with a short, narrow bunk bed. It’s all wooden, which Cynthia likes. She finds that the tops come off the built-in seats on either side of the table, and that inside them are long panels of cushioning, presumably to make up another, third bed. Opposite the table is a kitchen sink, a small counter and some cupboards they’ll keep food in. She opens a little door and finds a toilet, and a sink. The boat has everything a house would—a toilet, beds, sinks, only smaller and more fragile, like a tiny set of organs. It’s all perfect for Snot-head; he’s little too. At the back of the boat there’s a steering wheel, and an unsteady seat that flips out under it. There’s a ladder which can be pulled up or dropped into the water. Along the boat are bars to hold while you walk its perimeter, and a thin panel for your feet, one after the other. At the front there’s a washing-line, and a flattish area underneath where they can lie down, although of course it won’t be safe there for the dog.

This is what Cynthia has now: her boat, Anahera and Snot-head. Her money was like water, in its big nothingness and the way it slipped away before she really had it. She doesn’t mind. Money runs downwards, and people are always trying to position themselves under it like drains, but she’ll never involve herself in any of that ever again.

When Snot-head’s sniffed everything twice, he goes to sleep in the cabin. Cynthia crawls in after him, to touch the lift and fall of his little ribs. He’s a very soft dog, with a nose he only occasionally lets her touch and ears he can stick up but never does. He’s golden, and wrinkly, with a diva walk; he’s got a big little swingingly seductive bottom. Sometimes he likes to stretch his legs apart and press his crotch into the ground, that’s one of his cutest things. She lifts his ears and looks in them. They need to be cleaned, she’ll remember that. She shuts the cabin door quietly, and sits at the table to wait for Anahera.

They’re together, newly, looking at each other newly. Cynthia doesn’t know how to work the gas, so Anahera puts the kettle on, then she says, ‘We might not have any parties.’

Cynthia shrugs, that doesn’t matter. It was only something she said, not her dream. Anahera pours boiling water carefully over her coffee, and Cynthia’s herbal bag. The boat shifts gently right and left, and Anahera doesn’t adjust her body in any perceptible way.

‘Do you know my dog?’ Cynthia asks.

‘Yup,’ Anahera says. She’s lying down on the wooden bench, half obscured by the table.

‘Well,’ Cynthia says, and begins: ‘When I was fourteen I cried every single day. Sometimes three times. I wasn’t my best self then

, and I was bad-looking. I had no friends. I looked at myself in the mirror every day, crying. Sometimes I’d watch myself cry for whole half hours, in my pocket mirror, in my bed. I caught my tears in a jar, but they always dried up.’ She peers over the edge of the table to check Anahera’s listening, and Anahera sees her and nods.

Cynthia’s pleased. She continues: ‘And one day, my dad asked me what I wanted, you know. It was our best moment of love together. He didn’t hug me, but if he’d been that sort of guy I know he would have. He told me he’d heard my crying all that time. I felt better then, when I knew he’d been listening. He said, “What do you want? I’ll give it to you.”’

‘And?’ Anahera asks, although she must already know.

‘So I got Snot-head.’ He’s on her knee, looking up at her and listening. He looks like he’s been hit in the face with a plate, a bit. But that’s how he always looked. He’s just got a head that’s squarer than other dogs, with their pointy noses.

Anahera sits up, and nods again.

‘Yeah, and I still cried. But it was better. I always had Snot-head in bed with me, and he knew.’

‘That’s actually really nice,’ Anahera says.

‘Yeah. He’s my true love.’

‘Okay,’ Anahera says. ‘We’ll keep him.’

Cynthia hadn’t considered it up for question, but she nods.

‘Where will he shit then?’ Anahera asks, looking around their new boat.

Cynthia hadn’t thought of this.

‘In kitty litter,’ Anahera suggests.

‘We can get it tomorrow, he only needs to once a day.’

‘Okay,’ Anahera says.

The sea is gentle with their boat, and very blue. They find romantic novels in a little cupboard above the door, and read them together sunbathing on the deck, under the washing-line. The sun’s going down—so Cynthia goes around the side of the boat for blankets. There’s a loud thud, which Anahera says is just her weights. When it’s too dark to see they go back inside and Anahera makes some miso soup with broccoli and other stuff in it. The thudding happens again while they eat, but Cynthia isn’t frightened, she’s expecting it.

Baby

Baby