- Home

- Annaleese Jochems

Baby Page 13

Baby Read online

Page 13

She stays there all day, even though her phone goes flat at two and she never finds a comfortable way to sit. She doesn’t want to lie down. Anahera doesn’t join her till four, and when she does she says, ‘He’s sleeping,’ as if Gordon were a baby.

‘I hope you charged him,’ Cynthia says. ‘Two hundred dollars, that’s the price.’

‘We have to think in larger terms,’ Anahera says. Cynthia’s ready to march around the side of the boat and tell him what he has coming. But Anahera puts a hand on her leg and says, ‘To fund the sort of life you and I want long-term, we need money. Now, I can tell you for a fact that he’s got $12,000, minus what he’s already paid us.’

‘How do you know?’ Cynthia asks. The boat rolls over a wave.

‘What do you think I’ve been doing in there?’ Anahera gestures through the window. ‘I’m doing everything I can to get us what we need.’

‘I’ll help you seduce him, if that’s what’s necessary,’ Cynthia says sportively.

‘I should be able to do it,’ Anahera tells her.

That night they eat the fish. It’s crumbed and crumbling, buttered, and so, so very good. Cynthia makes sure not to look at Gordon while she chews.

35.

She’s in a dream of custard, and the bed’s empty. She rolls sleepily through the sheets and blankets, then gets caught in one and stops, waking. She remembers lapping the custard up in the dream, and loving it like a dog, but now the thought of lactose has sickened in her. Her feet are too hot. Her stomach’s uncomfortable to lie on. Her face is against the pillow, and she’s breathing back in the same air she breathed out.

Gordon’s saying, ‘Wonky, yes. That is it. Certainly it is on a lean, so I am telling you. But don’t worry. It is taking on water.’

Then, Anahera’s voice. ‘What do we do?’

A masculine sigh from Gordon. ‘I will tell you. I will lift the floor.’

Cynthia listens to Anahera snort, but then it’s a giggle. ‘She’s awake, I think. We can do it now.’

Cynthia can’t remember when they anchored, but the liquid feeling of her dream is underneath them, and the caughtness of waking in her tight sheets too; they’re moving, but not really.

‘Let her lie in her bed, and I will massage your poor foot,’ Gordon says.

Cynthia waits for Anahera to say no, or that she has to go for her swim. But she says, ‘Mmm,’ and her voice is only slightly doubtful.

‘Just give me a try,’ he says, ‘and we’ll see how it goes.’

Anahera doesn’t refuse, and there’s shuffling, then quiet. Cynthia thinks about waking up now, but it’s too late, they must have started. What could she say?

‘You see?’ Gordon says. ‘It is not so much a big deal, this foot. It is like I said.’

Anahera harrumphs, but almost happily, as if there’s been a joke and she’s taken a while to get it. Cynthia considers his repeated allegation of tilting. Does he think he’s something special, or deserves something special for noticing it? No boat’s going to sit perfectly straight. The real loss of balance is his weight, and their retention of him. Why do they need money at all? Cynthia refuses to think for an answer. She glares at the wall and thinks, Whore.

Anahera comes in to take a shit, and Gordon follows her. Cynthia lies silently, watching his back hunch to turn the stove on. He’s lumpish, and his head looks small, bent down under the mass of him.

She leans over, slowly, and grabs his leg. He jumps.

‘I love her, you know,’ she tells him. ‘But she’s disappointing me. Breaking my heart.’

He regains himself and his hunched posture quickly, and shrugs so his shoulders obscure his head completely. ‘She is a beautiful, cruel woman. What are we to do?’ He chuckles. Then he’s got the pot, and he’s putting oats in it. He doesn’t understand that Cynthia’s love for Anahera is serious and adult. She desperately wants to tell him they don’t want him, neither of them does, they only want his money. Instead she says, ‘Your muscles aren’t the hot kind, you know?’

He turns and smiles. When Anahera comes out of the toilet, Cynthia pretends she still has her dark black Gucci glasses, and that she’s wearing them. She looks from one wall to the other.

‘Tea?’ Gordon asks her. ‘You seem very stressed?’

‘I am, yes,’ Cynthia says solemnly, cryptically. He’s standing up straighter now, and he’s turned to face her.

‘It’s because the boat’s on a lean,’ Anahera says. ‘I know it’s been affecting me subconsciously.’ She speaks like she’s in a hurry to go somewhere.

‘No,’ Cynthia says. ‘I’ve just been learning a lot about human nature recently.’

Anahera chews her lip.

Gordon says, ‘It’s okay, you are only young.’

He gives her some porridge and she eats it slowly. They don’t have milk, they’re out of maple syrup, and it’s dry.

‘Can you feel it?’ Anahera asks her. ‘The lean?’

Cynthia shrugs, and puts another glum spoonful in her mouth. It’s hard to swallow, nearly impossible.

He turns and tells her, ‘I’m going to take up the floor!’ He’s finished his porridge. It’s easy for him, Cynthia thinks, because his mouth’s so huge and spitty. Anahera’s scraping the last of hers now too. Neither of them have noticed how much Cynthia hates her breakfast.

Anahera takes Gordon’s bowl and washes it, then her own. Cynthia puts hers between her legs on the bed and looks at them.

‘Are you alright, Cynthia-girl?’ he asks.

‘Yes, of course I am,’ she says. ‘I’m just sad at what I’ve learned lately, about people.’

Anahera doesn’t turn, or even shift her head. When she finishes washing the pot, she says, ‘Should we get started with the floor?’

Cynthia stands off to the side so they can switch the bed over. Anahera’s quick at it now. Then, she and Gordon get on their knees together, with Cynthia watching, and begin on the floor. There’s a layer of water-resistant carpet first, and under that panels of wood. One’s painted blue, and they shift it aside to reveal a pool of thick, murky oil-water. Immediately the air is overwhelmed with oil and rot.

‘You see, it is gunk!’ he shouts, as if he’s found something good. Anahera goes to get the flush-bucket from the toilet.

Cynthia makes a long, low, disgusted noise, and Gordon looks at her like he understands. They didn’t have to smell it before, and they do now. Why should they not have left it? Anahera fills her bucket up and takes it outside. While she’s gone, Cynthia notices again the silence of the weights in the ceiling above them. Gordon gets up and digs through the recycling. She asks him, ‘Did you shift her weights, after she told you not to?’

‘Oh,’ he says. ‘Oh yeah, I did.’ He finds an old milk bottle and saws the top off with a butter knife, retaining the handle. When Anahera comes back with the bucket he uses the bottle as a scoop to fill it with muck. Cynthia sits down at the table and re-examines her porridge. She’s hungry, so hungry now that she’d eat it without noticing the dryness. Now though, there’s the air. She’d vomit if she tried to swallow anything.

She stares at Anahera’s mouth and she doesn’t like it. It keeps almost twitching. Anahera stands slowly, and goes to dump the slosh in the sea. Cynthia considers it: the dark, potent murk running into the water. She wishes she’d planned more to say to Gordon about the weights, but she didn’t. Instead she goes and stands outside, watching the colours run and merge. Anahera comes out to rinse off the bucket, and Cynthia leans on the steering wheel. ‘He moved your weights.’

‘Oh,’ Anahera says, unbothered.

‘You know,’ Cynthia tries again, ‘I feel very ill. This is the second day in a row that he’s really stuffed up the air quality on our boat.’ Anahera looks confused, so Cynthia says, ‘The fish? The fish guts? I literally want to spew right now.’

Anahera shrugs. ‘The boat was on a lean. Do you know what that means?’

It doesn’t seem to mean much. ‘Quite p

olluting,’ Cynthia says, and nods at the water. There are flecks of rainbow on the surface, still being pulled away. Anahera puts an arm around Cynthia’s waist, and says, ‘What do you want to do today? Gordon’s paying us $800 for the next part of the Island Boat Tour.’

‘Why don’t you go without me, in the dinghy? He’ll pay more,’ Cynthia says, watching Anahera’s face. ‘Actually, I need some time alone.’

Anahera purses her lips, concerned, but shrugs. They go, like Cynthia said. Anahera winks as they leave—she was right then; they did get a bit extra.

She spends the rest of the day in bed, lulled by nausea. The air is tight against her and terrible with oil. Her whole body feels invaded by the slick black of it, but her suffering is too deep, and she’s too caught in it to move. She rolls onto her face. Then her side, her back, her other side, and onto her face again. She’s watched the whole of Bachelor Pad twice now, and Bachelor in Paradise doesn’t look as good. There’s no prize money on the sequel show. She’s tempted by an article on stuff.co.nz about a new Australian programme, The Briefcase (a take-off of an American one with the same name). Poor, suffering people are given money, but—twist!—they’re then shown footage of other poor suffering people, and asked if they’ll share some. Cynthia watches a trailer on YouTube. One family lost everything in a bushfire, and another woman had all her limbs amputated after a serious illness.

It’s been hours since they left and Cynthia feels dizzy.

Now, this isn’t why she’s upset, but why would Gordon choose Anahera? She can’t need or shiver like a girl, like Cynthia could, surely? Both he and Anahera are tan and muscular. What could be the purpose of a partnership between two people who both know how to lift things?

She gets up to pee, and checks her face in the mirror. It’s been a while since she has. She’s spotty and burnt now, with a dull, wild look in her eyes. Her hair’s scraggly from being washed in salt, and she’s got regrowth nearly two inches long. There’s new fat all over her, expanding under her skin.

She thinks about going to sit under the washing-line, but she’s worried that if they come back and she’s out there they’ll think she had a nice day in the sun. They don’t return till night. Cynthia can’t operate the gas oven, so she eats three packets of chips.

When they do come back Anahera brushes her teeth, then Gordon does his, although he doesn’t have a toothbrush. ‘So then, what did that guy Jason say?’ Anahera asks him, continuing some conversation from earlier.

‘Don’t know.’ Gordon pauses brushing to answer her. ‘I stopped listening a bit before then.’

Cynthia hoicks up some plegm. She hoicks and spits five times over the side of the boat, and she hopes they hear it. Then she stands outside the toilet, waiting for him to finish.

36.

Fear is only the healthy shock of remembering what’s important. Cynthia’s going to stage an intervention and sort out Anahera’s priorities. She doesn’t want porridge, so she asks Gordon to turn on the stove. He beams and does so. Anahera must be swimming. She makes omelettes. They look good, considering what she’s got to work with, and she’s proud. ‘Has Anahera eaten?’ She checks with Gordon.

He smiles again. ‘No.’

‘Have you?’ she asks nicely.

‘No.’ He smiles bigger.

She puts a tea towel over them to save warmth, and gets back in bed to spend a little time on Facebook. She’s turned chat off since they left, but she sometimes likes to scroll through the messages people sent her immediately after she did. They all say typical, lovely things: Where are you? Are you alright? Wherever you are we miss you so much? Why don’t you reply. Please, just let me know you’re alright, et cetera. Reading them is dreamy. She’s already deleted the one obnoxious one from an auntie, which mentioned her father.

When Anahera comes back Cynthia is in the perfect mood. They set up the table together, and sit down to the omelettes. ‘Delicious!’ Anahera says, and Cynthia knows she means it because they really are good, and they’re running out of food. Gordon nods and sits.

‘Anahera,’ Cynthia says. ‘It would be really nice if you and I could spend some time alone together today.’

‘Aha! Girl time!’ Gordon taps the table with his fork.

They both nod and laugh at him. ‘That’s exactly what I’ve been thinking,’ Anahera says.

He yawns, and no one mentions making him pay for the bed.

So they paddle together into the glistening water, and Cynthia’s tempted to say nothing at all. When they’re away from the boat, and nowhere in particular, she puts a hand gently on Anahera’s arm, signalling for her to pause. She does. Anahera is beautiful and kind. It’s hard to remember what she ever did that wasn’t reasonable.

But she’s looking at Cynthia questioningly.

‘How’s it going with him?’ Cynthia asks.

‘Good, I think. Just give me a bit and I’ll have it.’ Anahera rubs her thumb over the handle of her paddle and smiles.

‘Excellent, because the police are after us, and he’s a liability.’

Anahera shuffles back in her seat. ‘Really?’

‘Yep. Ron’s been texting me. I mean, we’ll be alright. But the last thing we need is Gordon coming along if we’re questioned.’

Anahera shuffles forward again. ‘What’s he been saying? Ron.’

‘His dad knows the family. They’re making investigations.’ As she’s speaking Cynthia realises that they are, of course they are—a boy’s dead.

‘What do they know?’ Anahera asks.

‘Nothing. He was last seen at the dairy, by the school. There’s a half coloured-in dick on the bottom of the slide at the playground, which they suspect is his. And an abandoned, nearly empty spray can there.’

Anahera nods, relieved, but Cynthia’s tummy wrenches. What if they were seen with Toby? What if the police talked to the boat salesman? They’d know the mooring number then, and the name and colour of Baby. She’s glad she took the photo from his office. Her face is hot, and suddenly she’s crying. Anahera moves forward to hold her.

‘It’s okay, we’ll send Gordon to get the groceries. We’ll make him get a dinghy-full. We’ll be fine. When we get enough money, and he’s gone, we’ll leave this place.’ But she adds, ‘Stop texting Ron.’

Cynthia nods. Maybe she should text him, just to check. ‘Okay,’ she says. ‘And you finish up with Gordon. I don’t care if we only get half the money, or three-quarters. This is important.’

Anahera nods seriously. They stay there for a long time. Cynthia puts her head in Anahera’s lap, and Anahera runs her fingers through her hair and says, ‘I’m sorry we didn’t get to talk like this earlier.’ Cynthia doesn’t mention the weights, or the toothbrush. Anahera’s saying the right things, and very kindly, but in a halting way. She keeps looking from Cynthia to the town, and back to the boat.

They paddle back slowly, with Anahera pausing intermittently to touch Cynthia’s face and say, ‘It’s okay. Don’t worry at all about it. We can go anywhere in our boat. Anywhere at all.’ Cynthia wants to grab her head and hold it still so they look straight at each other up close. She wants Anahera to confirm it wasn’t her fault, what happened with the boy. But she can’t ask, she’s too afraid. Something very good has happened between them, there on the dinghy, and she can’t afford to tip it even slightly.

When they get back they leave Gordon sleeping and watch an Adam Sandler movie on Cynthia’s phone. During a funny part, when they’re both laughing, she puts a hand on Anahera’s thigh. Later, when they’re laughing again she shifts it up and in, so it’s clasped between her legs. Anahera is beautiful muscle and clench, and she continues her laughing a moment after Sandler is off-screen.

37.

The next day she scrolls through her contacts several times, and can’t trust herself to trust Ron. Anahera’s not making visible progress with Gordon, but that doesn’t mean it’s not happening. She watches him a lot, and feels the need to interrogate him. Where did he

come from? What does he know? She understands; with every question asked she tells him something. He sees her looking, but stays friendly. That afternoon he catches another fish and Anahera guts it.

At night in bed Cynthia burns to speak, but she can feel Gordon alive in the cabin.

38.

It’s morning and he’s brushing his teeth again, loudly. Cynthia gets a glass of water, and through the crack of the bathroom door sees his mouth in the mirror. His teeth are clamped hard together, and he’s emitting foam through the gaps between them. She can’t see his eyes through the gap, just his jaw in the mirror and his big arm moving.

Anahera’s swimming. When Cynthia’s swallowed her water she opens a jar of olives. ‘I see you watching me,’ Gordon says, coming back out. ‘I see you watching me a lot.’

Cynthia shrugs, he’s on her boat.

‘It doesn’t matter if you like me,’ he says. ‘I am a social scientist.’

Whatever, Cynthia thinks, and goes to eat her olives under the washing-line. When she’s had enough and goes back in for something else, he says, ‘She left again, in the dinghy.’ Cynthia ignores him. He’s deconstructed the bed and made the table.

‘Look at this,’ he says, waving the boy’s cellphone.

‘What?’ She’s horrified. Didn’t he take it with him?

‘Asses,’ Gordon says, ‘and, tits.’

‘Why are you going through our things,’ Cynthia asks as calmly as possible. ‘In what world would that be appropriate?’

Gordon’s grinning and flicking through them. ‘An amateur, someone is,’ he says. ‘All on the desktop, I found them. In a folder titled “Homework”.’ He laughs, hard.

‘Anahera will be back soon,’ Cynthia says, ‘and I know she won’t consider it acceptable that you’ve been snooping through our stuff.’

‘Snooping!’ Gordon whoops. ‘I didn’t know it was your item. I thought it was a thing of the boat, you know—came with the boat.’ He gives her a sly look, and swipes right. ‘Oh,’ he says. ‘Oh gosh, yeah, there is one.’ He doesn’t show Cynthia what he’s looking at. ‘Right under my sleeping bed, it was, in the cabin. Only my second night, I found it. It is the same charge-hole as my own phone.’

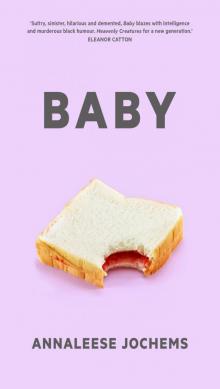

Baby

Baby